The EstateHistory

Nestled in the heart of North Wales, the Bodnant Estate sits within the Conwy Valley.

Nestled in the heart of North Wales, the Bodnant Estate sits within the Conwy Valley.

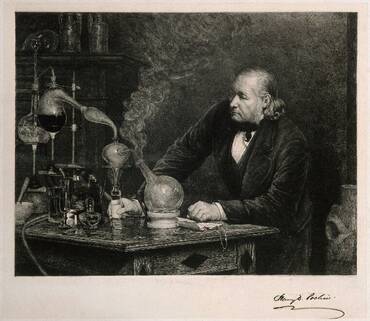

The son of a yeoman farmer from Leicester, Henry Pochin was a Victorian industrialist and chemist, he made his fortune by the invention of a process for clarifying rosin to produce coloured soap, and also the development of processes for the production of china clay from Cornwall. Pochin invested in industries such as coal, iron and shipbuilding, but he also used his wealth to improve working conditions for men and women and to provide relief during the cotton famine of the 1860s. As councillor and mayor of Salford, Pochin worked to bring gas lights to all homes, also to improve sanitation and reduce overcrowding. He founded the Salford Free Library and Museum and a Working Men's College.

Henry Pochin married Agnes Heap in 1852, she too had strong liberal views and was a staunch campaigner in the fight for women's suffrage, writing 'The Right of Women to Exercise the Elective Franchise' in 1855. Agnes spoke at the first ever public meeting on women's suffrage in 1868.

Throughout her life Agnes continued to write and lecture on women's rights, helping to found the Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage in 1868 and the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies in 1897. Agnes and Henry Pochin had six children, four sadly died in childhood, Percival and Laura were the two surviving children. After her father's death in 1895, Laura inherited the estate.

The Bodnant Estate was bought in 1874 by Henry Davis Pochin, a 50-year-old inventor and industrial chemist whose fortune had been made principally by soap. Pochin, a farmer’s son from Wigston in Leicestershire, had come up with a process for clarifying rosin, so that soap, which before had only ever been dull brown, could now be white – or even coloured and scented.

In the Victorian consumer boom, the commercial implications of this were vast, and Pochin sold the lucrative rights to his process to fund his second invention, a lower-cost method of manufacturing luxurious paper. This required china clay, so he bought a chain of china clay mines in Cornwall, and eventually amassed an industrial empire, ending up on the board of 22 firms, among the Clydeside shipbuilders John Brown & Co, various iron and coal works, and the London Metropolitan Railway, which built the first Underground line, and of which he was Deputy Chairman.

At Bodnant, he invested his expanding fortune and seemingly limitless energy into massive building works, encasing the white Georgian mansion in the blue sandstone of the current Bodnant Hall, refacing several of his farms in a similar Old English style, and building new cottages in the Eglwysbach Valley.

Bodnant Hall was at that time surrounded by 80 acres of beech-tree-filled parkland, and the picturesque but still wild Dell. Pochin laid the bones of the now-world-famous garden, planting redwoods and other exotic conifers in the Dell and threading paths along its steep valley sides, and embanking the romantic river Hiraethlyn with mossy masonry walls, so that it dashed with added foaming pace. He also built the famous Laburnum Arch.

But his bold sculpting of the landscape went far beyond Bodnant Garden, which was only the dense heart of a web of paths on his estate – smooth carriage rides up into the hills above the River Conway, or melodramatic clifftop walks, all carved to Pochin’s design.

Pochin had six children, but only two survived infancy, Laura (b.1854), and a son, Percival Gerard (b.1862), who had followed his father in training as a chemist. Pochin’s adoration of his only surviving male child is enshrined in a large 1872 painting (800 guineas, which would be £94,000 in today’s money) by R Ansdell RA showing Percy as a tow-headed lad, surrounded by white sheep. Ironically, Percy turned out to be a black sheep. The feckless prodigal son scandalised the old man so much that he disinherited him, and left everything to his bright, principled, business-like daughter Laura, who by then had married a Scottish barrister and Liberal MP, Charles McLaren, the nephew of the Liberal reformer John Bright and the grandson of Duncan McLaren MP, nicknamed “the Member for Scotland”. When elevated to the peerage in 1911, Charles McLaren took the name Aberconway, Welsh for “at the mouth of the Conway”, which is where Bodnant is.

As a teenager, in 1868, Laura had watched her mother Agnes propose a motion at the very first public women’s suffrage meeting. By the time she was 30, she was treasurer of the London branch of the National Society for Women’s Suffrage. It was useful having a parliamentary husband: she drafted the nine bills of The Women’s Charter which Charles introduced in the House of Commons in 1909. Laura was awarded a CBE for her work during WW1 in running a nursing home for officers in her London home. In 1933, when Laura died, The Times called her “one of the foremost horticulturists in Europe”, as well as “a capable woman of business, with the ready grasp and the courageous power of decision that enabled her to weigh big problems with the brain of a man”.

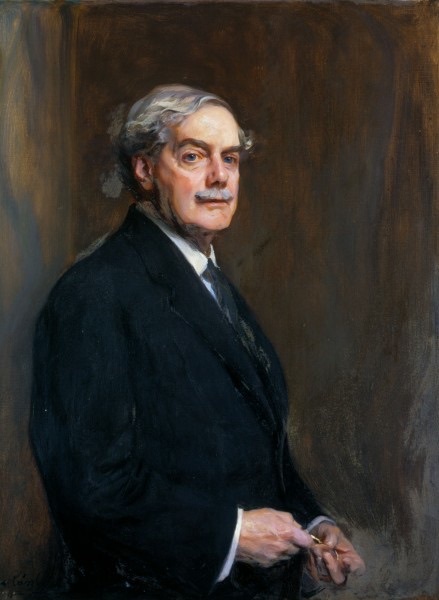

One of Laura's most momentous decisions was to give her son Henry, while still a student at Oxford, free rein in her garden. Things escalated when, in 1902, aged just 23, as he later put it, “I got hold of that nice material called squared paper on which you can make plans with a minimum of trouble,” and drew up the famous terraces.

Of all the personalities to have left their impression on Bodnant Garden, his is most deeply engraved. President of the Royal Horticultural Society from 1931 to 1953, his hunger for new plants and his astonishing – and untutored – flair for architecture transformed the garden, over his lifetime, into a showcase of rare trees and shrubs (most famously, rhododendrons) and an unexpected explosion of Italianate grandeur in North Wales.

His achievement at Bodnant is best summed up by Harold Nicolson, who wrote in his diary on August 18, 1952: "At Bodnant. A happy day. It drizzles a bit, but Vita [Sackville-West] and I are conducted by Harry [Aberconway] round the garden. He devotes his whole day to us. In the morning, we go round the dell, which is the most extensive, most varied and most tasteful piece of planting I have ever seen. We then go round the rest of the garden after luncheon. Then after tea we go through the nurseries and glass-houses. I have no doubt at all that this is the richest garden I have ever seen. Knowledge and taste are combined with enormous expenditure to render it one of the wonders of the world."

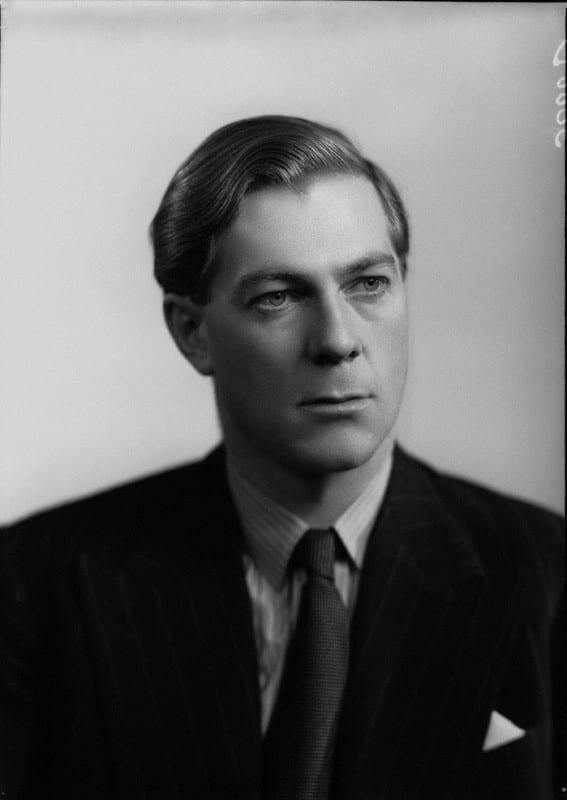

Charles Melville McLaren inherited the Bodnant Estate from his father in 1953. From a young age he was devoted to the estate and the garden at Bodnant, he recalled helping his father set up RHS flower show exhibits for the garden. Charles continued to develop the dramatic 80 acre Bodnant Garden with the National Trust, making improvements, opening up new views and adding new plants.

Charles read PPE at New College, Oxford and was trained as a barrister, being called to the Bar at the Middle Temple. During the second world war he served in the Royal Artillery and after the war he went into family businesses including John Brown Shipbuilding and English China Clays. Like his father and grandmother he was president of the Royal Horticultural Society, from 1961 to 1984.

Since his father's death in 2003, Michael McLaren KC (b.1958), a practising commercial barrister, now owns the Bodnant Estate and manages Bodnant Garden on behalf of the National Trust. The Estate is predominantly agricultural, with woodland and a few lakes, and also some mountain land in Snowdonia.

The main part of the Estate lies on the east bank of the River Conwy, centred on the Eglwysbach valley. West of the Eglwysbach valley, between it and the River Conwy, the Estate rises to about 767 feet (234m) at Mynydd Cauedig (or Garth Mountain), which has two lakes, fine views and good walking. East of the Eglwysbach valley, the Estate rises to about 1,118 feet (341m) at Moel Gyffylog, where there is an Edwardian shooting lodge and panoramic views of Snowdonia.

Some of the Estate lies in the flood plain on the west bank of the River Conwy. This includes the Estate’s largest farm, some woodland and two historic sites – an old Roman camp at Caerhun and an ancient Welsh camp at Bryn Castell.

The Estate also has some land high in Snowdonia, in the upper part of Cwm Eigiau, a wild and very unspoilt valley high in the Carneddau range of mountains. This runs from the lake (Llyn Eigiau) at an altitude of 1,312 feet (400m) up to the peak of Carnedd Llewellyn, which at 3,491 feet (1,064m) is the second highest peak in England and Wales and only slightly lower than Snowdon itself.

The Estate comprises about a dozen relatively small farms plus some smallholdings. All the farming is let out to tenant farmers, and none is kept in hand. The agriculture on the Estate, typically of the area, is predominantly the rearing of sheep, with some dairy and beef cattle. There is little arable farming.

Most of the woodland is hardwood, and much of it is mature or over-mature. Some of the woodland is categorised as “semi-natural ancient woodland” (predominantly sessile oak) and has changed little for centuries. The Estate’s policy is to attempt to manage the woodland more actively than occurred in the past, where possible on a continuous cover basis (as opposed to clear felling). However, very depressed timber prices and difficulties of extraction make the active management of the woodland a challenge.

There are over 20 miles of tracks through the woods and over the farms on the Estate. Except where there were existing footpaths and bridle paths, most of the tracks were made in the early 20th century by Henry Davis Pochin, so that his mother could drive her pony and trap into the hills. Guests at the Estate holiday lets are welcome to walk on all these tracks.

The Estate is also wonderful riding country, because of the dramatic lie of the land, the beauty of the scenery and the presence of all the Estate paths, and there are plans to develop equestrian activities.

There is fishing on three lakes on the Estate, including the largest (Llyn Syberi). The Llyn Syberi fishing is let out, but permits can be purchased from the Estate Office. There is also fishing on parts of the River Hiraethlyn and the right to fish on parts of the River Conwy.